The next series of blogs will explore what happened at the 27th Conference of the Parties (COP27) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate (UNFCC), which took place in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, over two weeks in mid- November. The UNFCC is the key international environmental treaty which sets the tone and ambition of action on climate for the 198 signatory countries, and by proxy, the business communities they regulate. Each year the COP produces a text to which all parties must agree. It is a highly political process which this year involved over 16, 000 delegates representing their country or regional parties, plus more than 17,000 additional observers from the UN Secretariat, intergovernmental organisations, non-government organisations and the media. The consensus appears to be that despite a landmark agreement on what’s known as “Loss and Damage”, discussed further below, the text was not reflective of the urgency and ambition now required by nations to keep global warming below 1.5⁰C.

Loss and Damage

What is it?

Loss and Damage refers to funding provided by developed nations to developing nations, as compensation for the losses sustained by those nations, who are typically least responsible for the climate crisis and simultaneously most severely impacted by it. They are sometimes framed as ‘climate reparations’ – compensation for the considerable historic emissions which are causing extreme weather events, as well as slow onset climate impacts like sea-level rise and melting glaciers, in the modern day. Such impacts are causing the loss of life, livelihoods, homes, food system security and physical territory, in nations which are already highly impoverished compared to the developed world. The funding would ideally work to collect and distribute cash quickly to areas afflicted by such impacts.

Why is it important?

Funding for loss and damage is a central tenant in developing nations’ demand for climate justice – climate action that deals with the inequal impacts of the climate crisis. They have been requesting that such funding be discussed at COP proceedings for almost three decades, but up until COP27, developed nations had blocked the request. It was perceived that if developing nations were put off again in this matter at COP27, there would be a loss of faith in the process in general, and furthermore, that the success of the COP overall would be marred by the failure.

How did it pan out?

For the first time, and after an “agenda fight” between parties before the COP even began, the conference agenda included an item to discuss “funding arrangements responding to loss and damage”. Historically high emitting parties like the USA and EU, whilst still recalcitrant, came to the table more open than they have been previously, perhaps influenced by the historic floods that recently ravaged Pakistan and Nigeria. Part of their concern is that they end up liable for potentially trillions of dollars’ worth of “Loss and Damage” claims. They also take issue with the fact the definition of developed and developing nations was determined by the UN in 1992, meaning the list of developed countries (who must provide the finance) only includes those who were members of the OECD in 1992, while the list of developing nations (who are eligible to receive finance) includes a wide range, from China, Russia and Saudi Arabia to Chad and Gabon.

The EU, therefore, stated they would agree to establishing “Loss and Damages” fund if it was based on the current wealth status of countries, so that relatively wealthy and high-emitting countries such as China would pay into it. They also insisted that it should focus on countries that are most vulnerable to climate disasters, rather than developing nations generally.

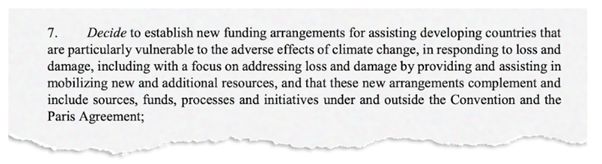

Over two-weeks of negotiations, various drafts were floated. Finally on the evening of Saturday 19th November (technically in “overtime” for the COP, which should have finished on Friday 18th) an agreement was reached that walks the middle ground between the demands of the developing nations (represented collectively by the G77) and developed countries. The finer details of how it will work, and who will pay into it, will be decided by governments over the next year. Importantly, however, the wording leaves room for additional donations to come from non-OECD countries. While not perfect, developing countries and NGOs have welcomed the outcome as momentous.

The final text of the “Loss and Damage” agreement is pictured below.

To start planning sustainably, contact us.

Better Planning. Better Planet.